Reading Sebald in Times of Genocide

Gustavo Racy

Author’s Note

The following text was first drafted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and went through different versions that featured various dates in its final paragraphs, as well as distinct images, arriving at a format close to the current one after October 7, 2023. Since the essay is the appropriate form for the ideas it contains, the text is an invitation for readers to reflect emotionally and affectively. Inspired by the work of Max Sebald, the essay is an experiment to make us feel and reflect on the invisible and not necessarily causal links that connect past and present and that, perhaps, foreshadow a future that haunts us.

Of Insensitivity, Virtue

When the Second World War was nearing its end, the British Royal Air Force and the U.S. Air Force dropped millions of tons of bombs on German territory. 131 cities were destroyed, 600,000 civilians were killed, and roughly 2.5 million houses were razed. In the wake of the massacre, in addition to the seven-and-a-half million homeless, “there were 31.1 cubic meters of rubble for every person in Cologne and 42.8 cubic meters for every inhabitant of Dresden” (Sebald, 2003: 4). As the German novelist argues, the numbers alone cannot convey the true magnitude of this devastation. Even postwar German literature failed to illuminate the events, omitting them from its reflections. According to W. G. Sebald (2003: 10), the reality of this destruction was repressed through collective and individual amnesia. Despite extensive photographic documentation of the ruined cities, “[t]here was a tacit agreement [...] that the true state of the material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described.”

Sebald (2003) interpreted the aftermath of the bombings as a process in which the Federal Republic of Germany pushed its prehistory to the back of its mind, enabling a reconstruction from zero while liberating itself from emotional entanglement. The prevailing discourse even attributed the success of this reconstruction to this very absence of emotion, which supposedly allowed obstacles to be overcome without showing weakness. For this reason, Sebald invokes Hans Magnus Enzensberger, according to whom German virtue became, precisely, insensitivity. They argue that even the German economic miracle would have been impossible without this unspoken mental condition, grounded in an unquestionable work ethic

learned in a totalitarian society, the logistical capacity for improvisation shown by an economy under constant threat, experience in the use of “foreign labor forces” [...] along with the centuries-old buildings accommodating homes and businesses in Nuremberg, Cologne, Frankfurt, Aachen, Brunswick, and Würzburg (Sebald, 2003: 12-13).

Just as nature bloomed anew amidst the ruins of Hamburg, Dresden, Frankfurt, Cologne, and Nuremberg, so too did social life. The natural history of destruction continued its course.

Angela Germin. Hamburg, July, 1943. Angela plays in the streets after Operation Gomorrah. CC-BY-SA 3.0. Deutsche Fotothek

To Make See and To Let Die

In 2018, I proposed the hypothesis that contemporary power, in its mechanism of making live and letting die explored by Michel Foucault (2005), also exercises a power to make see. Today, I would add that this power lets and makes us see through all the technological devices that centralize and fuse vision with other senses, imposing an inescapable visuality on virtually any event. It is often said the Vietnam War was the first televised war, though the Algerian War had already been documented visually in a sustained way. Today, any war and, more acutely, any genocide, can be broadcast live, not on television sets, but on smartphones within pocket’s reach, and consumed, sometimes involuntarily.

If, as Roland Barthes (1984) observed, there is a movement through which the reality of a representation comes to replace the thing represented, today we seem to have lost any index of truth, whether in the representation or in the referent. Factuality, materiality, the concrete and tangible thing, dissolves in the shadow of instant transmission that makes us see and lets us see everything. Such power asserts itself as a control over life and death, maintaining a productive order independent of the referent - of what is to be shown (and seen) - and dependent instead on the circulation and algorithmic games that mediate our seeing. Visuality (cf. Mirzoeff, 2006) imposes itself as a trigger for relations that surpass materiality and the linkage of facts and meanings.

Perhaps this story began with the emergence of photography and its index of realism, which made the mechanical reproduction of the external world possible. By becoming an index of reality, technical reproducibility imposed ways of seeing unconsciously aligned with ideological precepts. In the era of iconophagy (Baitello Junior, 2014), the abundance, proliferation, and centrality of images forestall any precise conceptualization of their possibilities and meanings. All meaning dissolves into desire, the only field still accessible under the unbearable pressure of stimuli, both formal and substantive. And yet, the digital images we consume daily engender a specific relational system, an articulation between producer, capitalist, apparatus, and audience that makes witnesses of us all. This means images still present themselves as a “system of relations between the inside and outside of langue, between the sayable and the unsayable in every language - that is, between a potential to say and its existence, between a possibility and an impossibility of saying” (Agamben, 2008: 146). By not speaking, or rather, by establishing themselves on the border between the potential and the existence of the sayable and the unsayable, images open a breach between subjects who, in turn, manage the potentials of speech. This relationship implies taking a stance, a decision before an image that, in itself, acquiring its own social life (Pinney, 1997), inhabits, perennially, the frontier of the sayable without assuming subjectivity.

Erich Andres. 1943. Vain refuge - people killed by the firestorm. CC-BY-SA 3.0. Deutsche Fotothek

Walter Benjamin, a philosopher dear to Sebald, reflects on the dialectical image, which he describes as a “dialectic at a standstill,” preceding distinctions between mental, visual, or material images: a third element prior to the differences between writing and figure, concept and metaphor. Unconfined by its form or content, and circumscribed only by the elements of its medium, the image presents something to perception and thus to knowledge. The contemporary image, therefore, shares a collective character that takes on a testimonial form, breaking with the idea of an impartial observer of the events it denotes and connotes. By promoting a distancing from form and appearance through its constituent elements, the image fosters “the resemblance between the figures of the external world and those of abstract knowledge” (Weigel, 1996: 51). This means the image inserts itself into history as a third term mediating the external world and knowledge, articulating its elements through its medium and thus acquiring new meaning at every moment.

The juxtaposition of sex and war on social networks exemplifies how the image endures, gathering all the elements presented to knowledge, unsayable in their totality. As an “ecosphere,” a space where words cease and images assume primacy, narrative gains a new dimension: the image travels materially, without a fixed point, through supposed elective affinities promoted by algorithms, which provoke eruptions of obscure meanings among the events of life, the world, and life in the world. If we pause to reflect, the pornographic eruption of images of sex and death in the contemporary world, punctuated by idyllic landscapes and cute animals that “spontaneously” appear, is constructed by the rupture of the logical chain of reality’s truth contents.

If, in the 1940s and 1950s, images of dead Germans were not enough to sensitize the German people and confront the trauma of their (self-)defeat, the digital images of the 21st century desensitize precisely because they do not present themselves as images, but as apparatuses and devices that capitalize on ruin. By pointing to insensitivity, Sebald - though he did not live to see smartphones and social media - unveiled a process we see consolidating today: the disappearance of the spectator as a participant in the event. By incorporating photographic records into his literature, Sebald developed a method that exposes ruptures in the logical chain of reality’s truth contents, revealing the frontier of the sayable at the very limit of language. Where language fails, where the structural chain of meaning collapses, the image must reverberate, returning to the observer the responsibility of testimony. In this sense, to observe must become to partake.

Optical unconscious, uncanniness. Against the emptiness produced by the profusion of images, they must reopen as a field for a reconstructive work that can be incorporated into human experience for the elaboration of reality and history. Reversing the Platonic motto that condemns the image as ontologically false: to make reality imagistic by restoring the witness. This would not mean taking images as testimonies of an absolute truth, but rather understanding their truth content, their sharing in reality; it implies a testimonial relationship through their very mode of production and their openness to the world, which involves the observer through the optical phenomenon in its physical (sensory) and social (seeing) dimensions, anchored on the border between the sayable and the unsayable, linear logic and dialectical perception. This promotes a caesura in the logical movement of thought, immobilizing it “in a constellation saturated with tensions” (Benjamin, 1991: 595).

Excursus - Means are Ends

At the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, Brazil had recorded 700,000 deaths. More than half could have been avoided had Jair Bolsonaro’s government adopted the measures recommended by the WHO and released emergency funds for precautionary measures, medical care, and financial aid for the vulnerable. His actions, largely supported by a significant portion of politicians and the population, led to the potential initiation of genocide charges, based on the understanding that the deaths were not merely a consequence of the pandemic, but a deliberate action, a neglect of the necessary care a government must provide: to let die and make die. The excuse of maintaining the economy, used by the Bolsonaro government, elevates to the absurd the power of the unspeakable, explainable in part by two reasons: first, a general and diffuse hopelessness, articulated confusedly, as statistical data showed that gatherings and risky behaviors from the outset mitigated infection curves; and second, by the parallel profusion of images that laid bare the social contradictions inherent in Brazilian society, from class to gender, race to geography.

Alex Pazuello/Semcom. Manaus, Brazil, March, 2020. Fotos Públicas CC BY-NC2.0.

Contemporary social media, reproducing both still and moving images, proliferate at unprecedented speed and volume the habits and behaviors of a society dependent almost exclusively on its own associative, collaborative, or individual initiative for the maintenance of life itself, a relative life, since it is worth asking whether the life imposed by the context (not only of the pandemic but of a fascist government) is indeed a life worth living. This proliferation, closely followed by numerous profiles dedicated to denouncing abuses and violations of safety measures on both social and traditional media, inevitably produced a sense of alienation and unfamiliarity with reality. While some of us could, privilege permitting, remain in isolation, others nearby crowded onto public transport, crammed into unhealthy housing, exposing themselves to a constant danger that the pandemic only rendered more visible.

The Observer as an Ethical Variable

Sebald notes that the origins of the bombing of German cities date back to Britain’s weakened position in 1941. At the time, Nazi Germany was at the height of its power, having conquered continental Europe and advanced rapidly into Africa and Asia. Left to its own devices, with little capacity to influence war plans on the already dominated continent, Churchill perceived that only heavy, total, and exterminatory bombing of German soil could draw Nazi forces back into a continental conflict, dividing their military resources on yet another front. The means to carry out such an attack were scarce, almost non-existent. Various extreme plans were devised until, in 1942, the most feasible strategy of aerial bombardment was sanctioned by the government, aiming at the total demoralization of the enemy’s civilian population and its industrial workers.

However, the directive did not arise from a desire to end the war quickly. Rather, it was likely the only means available to intervene in the conflict. It later emerged that, on the eve of 1944, Allied intelligence perceived the enemy’s morale as unshaken, while industrial production (which, if properly targeted, would have paralyzed the entire German system, according to Albert Speer himself) was only marginally impeded. It is also estimated that the material and organizational effort of the aerial offensive may have consumed one-third of British war production to reach its peak destructive capacity.

Once the matériel was manufactured, simply letting the aircraft and their valuable freight stand idle on the airfields of eastern England ran counter to any healthy economic instinct. And a conclusive factor in deciding to continue the offensive was probably the propaganda value, essential for bolstering British morale (Sebald, 2003: 18).

The attack, the air war, continued despite the possibility of precise long-range strikes on the industrial complexes of major German cities, under the command of Sir Arthur Harris, by all accounts, according to Sebald’s sources, a commander passionate about war. The exorbitant cost of war production could not lie idle; the victims of war were not “sacrifices made as means to an end of any kind, but [...] both the means and the end in themselves” (Sebald, 2003: 19–20).

It is unsurprising, therefore, that Sebald is so attentive to silence. Considered, like Walter Benjamin, “a foreigner of indeterminate nationality, but of German origin” (cf. Gagnebin, 2007), Sebald shapes the testimony of modern reality through a sometimes archaic, spectral discourse aimed at the “not entirely obvious omnipresence of suffering” (McCulloch, 2003: 2). This form aligns with the Freudian uncanny [Unheimliche] through phantasmagorias revealed by the juxtaposition of anachronistic elements: excerpts, quotations, photographic images, facsimiles, and reproductions articulated, as in a bricolage, to shape the testimony of what is conveyed through apparent free association. Sebald is the first witness of his accounts, not by narrating them directly, but by making explicit to the reader/observer his own implication in the events that unfold like an avalanche before their eyes, whether turned toward the past or fixed on the present.

Walter Hahn. 1945. Dresden - Bodies cremated in the Altmark after RAF and USAF bombing. CC-BY-SA 3.0. Deutsche Fotothek

The silence to which Sebald refers is broken, within his texts, by imagistic interruptions that provoke the shock necessary to activate the work of memory. By denouncing the silence of the unspoken through the interruption of the image, Sebald elaborates the uncanny phantasmagoria of German trauma by showing it as sayable, albeit through another medium. These images reveal an indexical character that shows reality as it was constructed, even if it has not always been or is not always the same. Regardless of the possibility of technical manipulation, photographs trigger relationships and affects that acquire meaning only through the evocation and elaboration of prior elements that shift sense beyond the merely figurative. After all, as Susan Sontag remarked of Sebald’s literature, “[f]iction and factuality are not, of course, opposites” (Sontag, 2000: n/p.). Consciously or not, images perform an archaeological work of elaboration from ideological elements evoked by memory and free association, informed by general culture. Acknowledging this, however, is an ethical variable. Like Nietzsche, Sebald knew that not everyone could read him.

Excursus II - Grandville

Hans Erich Nossack, an author awarded the Georg Büchner Prize and frequently cited by Sebald, recounts that in July 1943, three months after the bombing of Hamburg, one could observe people engaging in everyday activities as if nothing had happened. In an unaffected neighborhood, he even saw groups sitting on balconies having coffee, like “the sight of Grandville’s animals, in human dress and armed with cutlery, consuming a fellow creature” (Sebald, 2003: 42). To Nossack, this seemed absurd and shocking. At the same time, it is known that maintaining daily routines,

[f]rom the baking of a cake to put on the coffee table to the observance of more elevated cultural rituals, is a tried and trusted method for preserving what is thought of as healthy human reason. The role of music in the evolution and collapse of the German Reich is part of this context. Whenever it seemed advisable to invoke the gravity of the hour a full orchestra was conscripted, and the regime identified itself with the affirmative statement of the symphonic finale. The bombing of German cities made no difference. Alexander Kluge remembers a performance of Aida broadcast by Radio Roma the night before the raid on Halberstadt (Sebald, 2003: 42).

Alex Ferro. Illegal party in Rio, February 20, 2021. Alex Ferro/VEJA, courtesy of the author.

As I write this essay, I am accompanied by the shadow of the long pandemic days in Brazil, hand in hand with the days that have stretched on since October 7, 2023. I am struck by a strange familiarity with a continuum that aligns me with the dead of Hamburg and little Angela. In the northern hemisphere, the dog days linger. In the south, the cold will soon arrive, condemning countless homeless to death by hypothermia. We study the order of things without grasping their essential meanings. What seems disconnected (an aerial bombardment, a viral plague, and a colonial genocide) appears to me as events unfolding from the same catastrophe.

There seems to be a pattern, a repetition in which everything happens the same but a little differently, made clear by the images that inhabit the vast contemporary digital environment. Present images (Favero, 2018) reposition, re-signify, and actualize themselves according to the observer’s position and power. As Sebald (1995: 18) said of Thomas Browne, in this continuum “of devouring and being devoured, nothing endures.” I think of how many names have been consigned to oblivion, and I remember what I myself have forgotten. I understand, in the eruption of images of mass graves and a devastated Palestine, the tension-laden suspension of the instant, which, unknown and not yet sayable, calls for my care and alertness. This strange familiarity impacts me as trauma, acting like a foreign body of constructed memory, from past days that extend into the present and whose form is lost in the repetition of routine. Before the image, I see myself as if I were another, because the other I see is there by mere contingency. More than unfamiliar, I feel like a stranger, a migrant wandering through terrains where image and reality blur and show me everything and nothing. Almost as if anticipating the loss of future memory, I cling to images, like Sebald, aware of their falsehood. But I perceive something greater: their readiness to work with me, calling me to resist silence in the most silent way possible. I feel, perhaps, the call of the dead I see in images, in other times, present or absent.

As I conclude this essay on June 28, 2025, I recall that exactly 927 years ago, the First Crusaders were defeated in Palestine. 665 years ago, Muhammad VI became the tenth king of Granada, in the last gasp of Al-Andalus before its end. 160 years later, Charles V would become emperor, defining the course of our modern history, now dominated by Europe. I also remember that on this same day in 1635, France made Guadeloupe its colony, and in 1720 the Vila Rica Revolt began. In 1778, the US War of Independence reached its turning point with the Battle of Monmouth, and on June 28, 1838, Victoria was crowned Empress of the British Empire. Finally, I remember that on this same day, 111 years ago, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo.

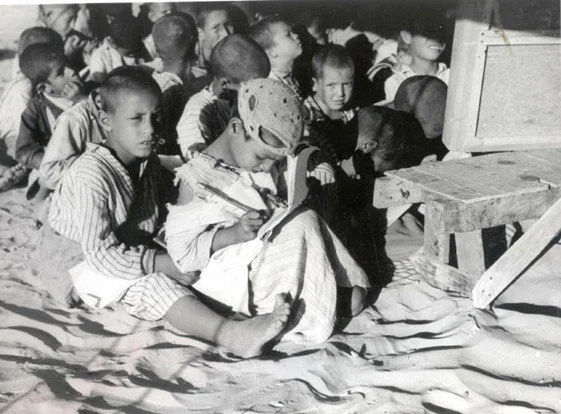

Anonymous Photographer, 1948. Palestinian siblings in a school for refugees. Wikicommons

In his literary and imagistic thinking, Sebald showed us, paralleling the central paradigm of contemporaneity discussed by Giorgio Agamben (2008), that where language falters, images summon. In doing so, he gave voice to the silence that threatens memory and elaboration, unlocking the immanent potential of the image to counter the unsayable. Like Walter Benjamin (1995–2000), Sebald apprehends the future in the mode of the French tense of the future anterior (Symons, 2020), discerning in the smallest detail what “will have been,” thus fulfilling his primary task: to resurrect what was erased, relegated, and dead.

[F]or it is hard to discover

the winged vertebrates of prehistory

Embedded in tablets of slate.

But if I see before me

the nervature of past life

in one image, I always think

that this has something to do

with truth [...]

(Sebald, 2002: 83)

Bombyx Mori

We know the direct consequence of the Archduke’s assassination: the disintegration and reorganization of so-called democratic societies in Europe and the United States through Auschwitz and the Cold War, with all its proxy wars and neo- and sub-imperialisms, culminating in the dismemberment of various world regions into parcels subjected to the harshest exploitation. This logic finds a new dynamic in the genocide perpetrated by the Zionist entity against Palestine. As the last survivor of 19th-century nationalism, the purest project of European domination, it crushes a people who, like others, resist fiercely. This reveals that, after the era of resistance, liberation has become necessary.

Zionism wages a war of images by all available means, yielding spectacular capital turnover for large corporations while undermining the production, circulation, and dissemination of images of Palestinian reality, as well as Sudanese or Congolese reality. The genocide has continued since and before 1948, and we do not know if it will cease. If it does not end today in Palestine, Sudan, or Congo, it may begin again tomorrow against the Indigenous and Black peoples of Abya Yala, the ethnic minorities of the Asian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, the Indigenous peoples of the polar circle. By the time you finish reading this text, more and more people will have been swallowed by the perverse wheel of capital and colonialism. In the images that persist, a content of truth dwindles; we are blinded, desperately seeking the image that, as evidence, will expose the terror. But such an image exists only momentarily, for, as in postwar Germany, our insensitivity is made a virtue under the mask of empathy. To read Sebald in times of genocide is to understand that by assuming ourselves as integral parts of the scenes within images, we can witness not what has occurred, but what must not happen—as the eponymous protagonist of Austerlitz, the author’s final work, attests:

It seems to me, then, as if all the moments of our life occupy the same space, as if future events already existed and were only waiting for us to find our way to them at last, just as when we have accepted an invitation we duly arrive at a certain house at a given time. And might it not be, continued Austerlitz, that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time, so to speak? (Sebald, 2001: 257-258).

References

Agamben, G. 2008. O Que Resta de Auschwitz: o arquivo e a testemunha (Homo Sacer III). São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial.

Baitello Junior, N. 2014. A Era da Iconofagia. Reflexões sobre imagem, comunicação, mídia e cultura. São Paulo: Papirus.

Benjamin, W. 1995-2000. Gesammelte Briefe. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp

_______. 1991. “Das Passagen-Werk.” R. Tiedemann (org). Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften (Vol. V. I.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Enzensberger, H. M. 1990. Europa in Trümmern. Frankfurt am Main: Eichborn.

Gagnebin, J. M. 2007. “Walter Benjamin, um estrangeiro de nacionalidade indeterminada, mas de origem alemã’.” M. Seligmann-Silva (org). Leituras de Walter Benjamin. São Paulo: FAPESP; Annablume.

McCulloch, M. R. 2003. Understanding Sebald. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Pinney, C. 1997. Camera Indica. The Social Life of Indian Photographs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sebald, W. G. 2003. “Air War and Literature." On the Natural History of Destruction. Anthea Bell (Trans.). New York: Random House.

_______. 2002. After Nature. Michael Hamburger (Trans.). New York: The Modern Library.

_______. 2001. Austerlitz. Anthea Bell (Trans.). New York: Modern Library.

_______. 1995. Des Ringe des Saturn. Eine englische Wallfahrt. Frankfurt am Main: Eichborn.

Sontag, S. 2000. A Mind in Mourning. Available at https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/mourning-sickness/ - accessed in 28/06/2024

Symons, S. 2020. “Apresentação”. G. Racy (org). Walter Benjamin está Morto. São Paulo: sobinfluencia edições.

Weigel, S. 1996. Body- and Image-Space. Re-reading Walter Benjamin. London: Routledge.

Gustavo Racy is a professor at the Department of Anthropology at the Federal University of Paraná. He has a PhD in Social Sciences (University of Antwerp, 2018), and is a researcher on visual culture, capitalism, and political anthropology. Since 2024 he is the co-director of Al Jaliah.